By David Waksberg

Originally from the j. Jewish News of Northern California

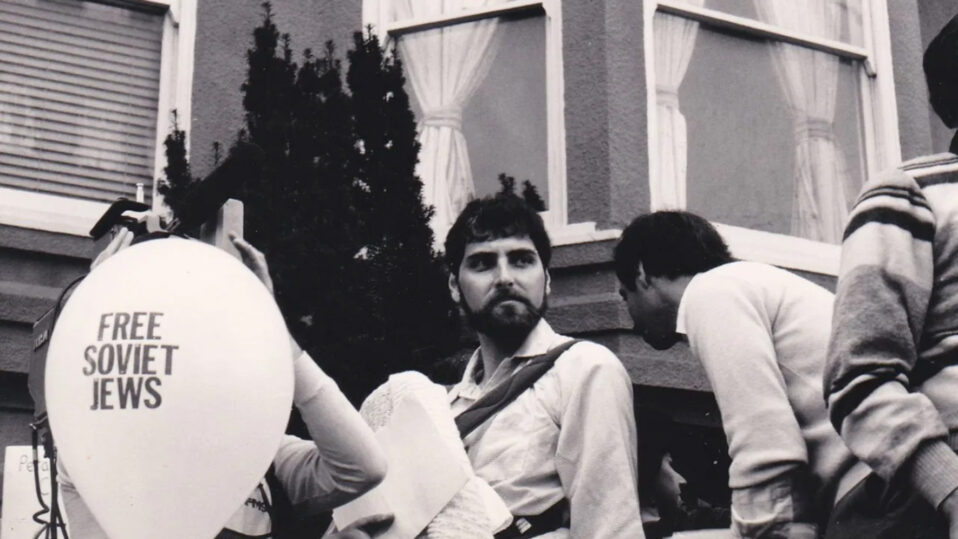

When I was a teenager, I wore a huge Jewish star around my neck, and on it was the name of Mark Dymshitz, a Soviet Jewish prisoner of conscience.

One day, an African American friend of mine stopped me.

“Why do you wear that star around your neck?”

I explained who Mark Dymshitz was and how I wore this thing to call attention to his plight and that of Soviet Jews. And, I added, I wore a Jewish star so people would know I’m Jewish.

He thought for a moment. Then he said, “Yeah, I get it,” and, rubbing the skin on his face, he continued, “That’s why I wear this, so people will know I’m black.” We both laughed.

He understood that my star was a badge of identity; a badge I could choose to wear or not wear. He had no such choice; his skin was literally in the game.

It was the civil rights movement that first inspired me to become a Soviet Jewry activist, and Black Pride that influenced young Jews like me to wear our Yiddishkeit on our sleeves, or in my case, around my neck.

Later, I understood a deeper irony. I was fighting for the rights of Jews in a land that persecuted them. I was waging that struggle from a free country to which my grandparents had fled. A country that had welcomed them after they had run from a land that never accepted them. Here, my family felt safe and whole. Back in Poland, they never did and every loved one they left behind was slaughtered. Here they arrived, so I could grow up in freedom. That was my family narrative. The American Jewish Dream.

My black friend grew up in the same place as I. His was a country that had kidnapped his ancestors, placed them in chains and enslaved them for half of their time on this soil. After they were freed from bondage, they lived as second-class citizens. Our dream was their nightmare.

It wasn’t until college that I met Jews of color and began to understand that among my own people, our experiences of this country were profoundly different. For some of my friends, my family’s goldene medine (golden land) was their Mitzrayim (Egypt).

My struggle to free Soviet Jews continued for many years. And throughout those years I’d hear from critics that it really wasn’t that bad, that we exaggerated the anti-Semitism, that it was in our heads, that we were practicing victim or grievance politics. Myths were created to deflect criticism, myths that presented a false narrative of equality. After the trauma comes the gaslighting.

Myths have been in force here too: Discrimination is over. We even elected a black president! Stop complaining and get on with it!

It wasn’t until college that I met Jews of color and began to understand that among my own people, our experiences of this country were profoundly different.

That sound you’ve been hearing is the shutting of minds and blaming of victims. I have heard it before.

As for anti-Semitism in Russia, I knew the truth. The truth was worse than it appeared. It usually is. Still, that gaslighting, it’s like a second arrow— there’s the persecution itself, and then there’s the denial, which hurts nearly as much. We Jews have experienced many traumas through history, and much gaslighting, as well. And the denial makes you feel … alone.

That’s why non-Jews who spoke out on our behalf were so important. It felt validating. Like that day two years ago, after the Pittsburgh massacre, when non-Jews came to our Jewish community gathering and spoke out. I don’t remember what they said. But I remember how it made me feel. It made me feel less alone.

And that’s why I believe it is important that white Jews speak out now, after the murders of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor. Here, too, myths present a false narrative of equality, blaming victims, obscuring how racism is institutionalized. Don’t believe the myths. Once again, the truth is actually worse than it appears. And I want, at least as a start, for people of color to feel less alone.

Our ultimate goal must be to make it safe for someone to drive or to jog or, in the case of Ms. Taylor, to lie in their bed while black.

Change will come. The road will be long and hard and involve addressing hard questions. Like why, among those arrested, is the rate of fatalities among black people so much higher than that of whites? It’s not just a few rogue cops. Why does a pandemic so disproportionately attack people of color? Could it be inequities in our health care system? These trends did not begin with Covid-19.

A half-century ago, Elie Wiesel and others called upon American Jews to open our hearts and minds, and expand our circle of caring to Jews we never met who lived 10,000 miles away. We rose to the task. We knew that a real remedy would require deep structural change in a totalitarian regime.

But in the short term, we employed a few strategies that led to that deeper change: We educated ourselves about the nature of Soviet oppression and anti-Semitism. We listened to Soviet Jews, and we honored their experience. We spoke out because we knew too well where silence would lead.

Now, as then, I suggest we begin with education, with listening, because most of us have no idea what white privilege means — because our experience is our default. We learn by listening to those who suffer the absence of white privilege each day. That can start with our own people. Jews of color in my own congregation — their experience of this country, of law enforcement, and of our own community are different from my own.

And we must speak out.

“Do not stand idly by the blood of your neighbor,” the Torah says (Leviticus 19:16). That verse calls me, once again, to examine who is inside my circle of caring. Something is terribly wrong in our country and it has been for a long time. I feel called now by the Floyds, the Arberys and the Taylors as I felt called then by Mark Dymshitz.

There are enormous differences between being black in this country and being Jewish in the USSR. But both the U.S. civil rights movement and the Soviet Jewry movement were inspired by the Exodus from Egypt. “Let My People Go,” sang African American slaves. We still sing it at our Passover seder. And “Let My People Go” became the Soviet Jewry movement’s catch-phrase.

I don’t want people of color — Jews and others — to feel alone. I want, at my Passover seder, to be able to sing Avadim hayenu, ata bnei horin (we were slaves, now we are free) and know that includes all of us.